Amid escalating regional tensions, voters in the self-declared state of Somaliland will vote on Wednesday in its fourth general election since its 1991 break from Somalia. While Somaliland now has its own government, parliament, currency, passports and other features of an independent country, however, its sovereignty remains unrecognised internationally as Somalia continues to view it as part of its territory.

In the capital city of Hargeisa, supporters of the ruling Kulmiye (Peace, Unity and Development) Party crowded the streets in green-and-yellow-coloured shirts, chanting victory songs, with women ululating as the campaigning ended last week.

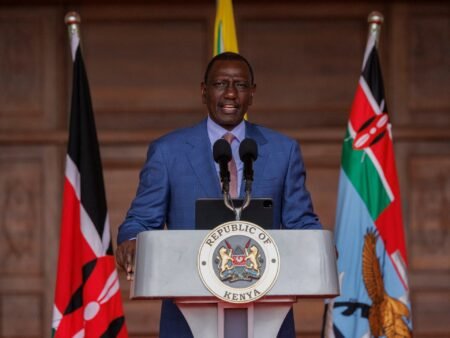

Incumbent President Muse Bihi Abdi is seeking a renewed five-year mandate in the election, delayed by two years because of time and financial constraints, according to authorities. His main challenger is former parliament speaker and opposition candidate Abdirahman “Irro” Mohamed Abdullahi of the Somaliland National Party, also known as the Wadani party, which has promised more roles for women and young people in his government.

The rising cost of living and territorial tensions with rebels in the disputed Las Anod, claimed by Puntland, another autonomous region that broke away from Somalia in 1998, have emerged as the key issues in the run-up to the election.

Crucially, the vote is also being shaped by the candidates’ international weight and what that could do for Somaliland, which is desperate to be recognised as a separate country.

President Abdi has touted his administration’s landmark “port-for-recognition” memorandum of understanding (MOU) for a deal with neighbouring Ethiopia, signed in January by him and Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. The proposed deal would allow the larger, landlocked Ethiopia to use Somaliland’s Red Sea port of Berbera. In return, Ethiopia has said it will undertake an “in-depth assessment” of Somaliland’s quest for official recognition. In literal terms, Ethiopia has not specifically said it will recognise Somaliland. However, authorities in Hargeisa see eventual recognition as the outcome.

The historic maritime MOU has caused anger in Somalia, and relations between Ethiopia and Somalia have since virtually collapsed. In October, Ethiopian diplomat Ali Mohamed Adan was expelled from Somalia in what is just the latest in a long list of back-and-forth diplomatic spats.

Irro has capitalised on this fallout, blaming Abdi for being a divisive actor.

Egypt – Ethiopia’s longtime rival – and Turkey, a close ally of Somalia, have waded into the fray. Turkey has taken on the role of peacemaker by facilitating talks, while Egypt is backing Somalia by providing military aid.

“The situation has got more tense with other actors getting involved,” Hargeisa-based political analyst Mousafa Ahmad told Al Jazeera. “I am not sure how the deal will go through. I’d say it is very unpredictable.” There is currently no set date for the deal to be made official.

The port deal: International recognition for Somaliland?

Ethiopia, Africa’s largest landlocked nation by population (more than 120 million) has relied exclusively on tiny neighbour Djibouti’s ports to access the Gulf of Aden for some time. After a three-decade-long war, Eritrea seceded from Ethiopia in 1993, causing the country to lose access to coastlines, something authorities there have always seen as hobbling its regional “big power” status.

Addis Ababa has since then sought more direct access to the important maritime routes around it, looking to diversify from Djibouti’s offerings. Last October, Prime Minister Abiy told parliament Ethiopia was surrounded by water but remained “thirsty”. Accessing the Red Sea and the Nile would secure the country’s future, he said.

Under the Somaliland deal, Ethiopia will take a 50-year lease of the Berbera Port, affording Addis Ababa 20km (12.5 miles) of the Red Sea coastline for commercial marine operations and a naval base. The port was redeveloped in 2018 by Dubai firm and port manager DP World, which holds a 51 percent stake in its operations. Hargeisa owns a 30 percent stake in the public-private partnership, while Addis Ababa has now acquired a 19 percent stake.

In addition, Hargeisa will also receive a stake in the state-owned Ethiopian Airlines, according to the January deal, although details about this part of the agreement are still scant.

Official recognition from Ethiopia could pave the way for global recognition, some analysts say, and lead other countries to trade with Somaliland or open embassies there.

For Hargeisa, the deal appears as good as done. “We are ready and just waiting for Ethiopia to sign the deal,” President Abdi told reporters on the campaign trail earlier this month. Authorities are trying to market the port as an alternative avenue to the Suez Canal where ships face attacks from Houthi rebels. Locally, it’ll be an economic “game changer” Abdi has said, and is set to unlock about $3.4bn in revenues.

A power change is unlikely to roll back local enthusiasm for the deal, analysts say, although the Wadani party has criticised Abdi for handling the deal with Ethiopia in a divisive manner. “From the Somaliland side, the deal is still on and will be on even if there’s a change of government and Wadani wins the elections,” Ahmad said.

When will that happen is another question entirely, though. Amid the regional fallout, Ethiopia has not yet put a date on when the lease will take effect or when it would officially recognise Somaliland – in what some say might be an attempt to slow down the process and not immediately escalate tensions.

Enemies in alliance?

One day after the Somaliland port deal was announced in January, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperations (MFA) in Mogadishu issued a statement declaring it “outrageous” and “blatant transgression” by Ethiopia, and that Somalia would not cede “one inch” of territory.

“We will not stand by and watch our sovereignty being compromised,” President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud declared, addressing lawmakers in parliament. The same day, Ethiopia’s ambassador was sent home.

Somalia also turned to Egypt – which is already at loggerheads with Ethiopia over a controversial $4bn dam project on the Blue Nile River. The dam controversy dates back to 2011 when Ethiopia began constructing the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) near Guba in hopes of producing some 5,000 megawatts of additional electricity from the Nile – double the current availability for its energy-starved population.

Egypt, which also relies on the Nile, has vehemently opposed the project, arguing that the dam would devastate its water supplies for agriculture and domestic use. Talks between the two countries have stalled, with Cairo accusing Addis Ababa of being too rigid and threatening to “defend Egypt”. Ethiopia has stubbornly pressed on and began generating electricity from the dam in 2022.

In August, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi signed a defence pact with Somalia’s Mohamud to bolster security. During a summit in Asmara in October, el-Sisi and Mohamud joined Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki to pledge greater cooperation over regional security.

Cairo has since delivered heavy military equipment, including weapons and armoured vehicles, loaded on several planes to Mogadishu in August and September, in an apparent show of force that has angered the Ethiopian government.

The military pact comes just as the African Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) comes to an end this year. The peacekeeping mission, supported by the African Union, has been largely led by Ethiopia, which provides 4,300 soldiers. It began in 2007 to defend Somalia against the armed group al-Shabab. Uganda, Burundi, Djibouti and Kenya have also contributed troops.

Mogadishu has announced that Ethiopia is the only country not to be included in a separate replacement mission that will begin its mandate on January 1, 2025. Meanwhile, Cairo has announced that it is willing to deploy some 5,000 personnel to join the new formation. Egypt was not involved in the first mission.

Other countries have also entered the row. Turkey, a longtime ally of Somalia, has attempted to play peacemaker, mediating several rounds of talks in Ankara that have largely stalled and are now indefinitely postponed. Turkey maintains a military base in Mogadishu.

Tensions between Djibouti and Ethiopia are also mounting. Djibouti, like Somaliland, lies to Ethiopia’s east and shares a border with the breakaway region. The small country relies on its shipping industries for revenue and is also angered by the proposed deal between Somaliland and Ethiopia, which it sees as taking away a main source of income. Presently, Djibouti processes more than 90 percent of Ethiopian maritime trade.

Officials there have also condemned Hargeisa’s allegations that it is funding, training and arming rebel groups from Somaliland’s Issa and Gadabursi clans who are seeking to control territory. The accusations were made after January’s port deal MOU.

‘No recognition, no deal’

Analysts are warning tensions could escalate as far as possible military action between regional superpowers – Ethiopia and Egypt – if the situation does not cool down.

“If the Egyptians put boots on the ground and deploy troops along the border with Ethiopia, it could bring the two into direct confrontation,” Rashid Abdi, a Kenya-based analyst with the Sahan Research think tank, told the Reuters news agency. “The threat of a direct shooting war is low, but a proxy conflict is possible.”

To calm tensions, some experts have cautioned Ethiopia against recognising Somaliland officially while still leasing its port.

“Ethiopia can access the sea through Somaliland without formal recognition,” writes analyst Endalcachew Bayeh in the academic publication, The Conversation, adding that both powers must reconsider their strategies and “exercise restraint”.

Although Ethiopia sent an ambassador to Hargeisa in January, right after the port deal MOU was signed, officially making it the first country to do so, it has not yet signed the final port lease and has not taken further significant steps.

Meanwhile, Somaliland authorities reiterate they are ready to officially start the port agreement with Ethiopia despite the regional pushback. In apparent solidarity with its new ally, Somaliland shut down an Egyptian cultural centre in Hargeisa in September.

Taking the recognition deal off the table is simply a non-starter for Somaliland, analyst Ahmed said.

“Somaliland government and people are very clear about this – the recognition is the starting point for the cooperation,” he said. “From Somaliland’s perspective, it’s no recognition, no deal.”

Read the full article here