It’s the night of Sydney’s metamorphosis. Orderly inner-city streets lined with bars and clubs are awash in glitter, strobe lights, food trucks and block parties. This year, the transformation will take place on February 28 – the night of the 48th Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade.

The annual festival, embraced by revellers donning the smallest, sheerest, sparkliest and most feathered costumes in their wardrobes, is the night-of-nights for the city’s queer community. This year’s theme, ECSTATICA, is about capturing the feeling of collective release when queer communities freely move and gather in public spaces with joy, pride and defiance.

More than 10,000 people are expected to march across 160 floats showcasing the vast array of queer subcultures, organisations and diversity in Australia and beyond. Last year, about 300,000 partygoers attended the event, generating $38 million for the local economy.

But as Mardi Gras has grown to become one of Australia’s largest cultural institutions, so too has the chorus of criticism.

This year’s event has been hit by claims the organisation is not prioritising queer-led operators, public funding woes leading to the cancellation of Mardi Gras’ signature after-party event, an internal board feud and a political spat in state parliament.

So, what is behind all this disquiet, and can Mardi Gras overcome the turbulence to put on another dazzling show?

The first Mardi Gras

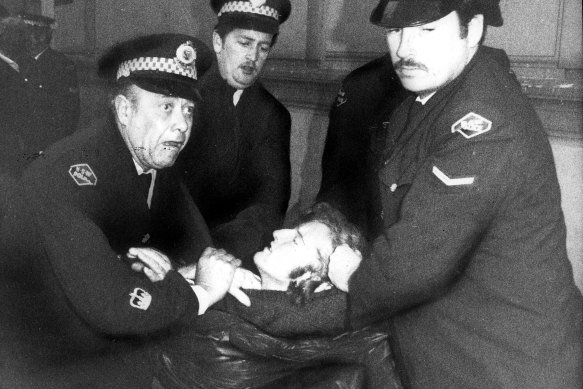

On June 24, 1978, more than 500 activists took to Taylor Square in Darlinghurst, supporting New York’s Stonewall movement and calling for the decriminalisation of homosexuality and an end to discrimination. The march that became the first Mardi Gras ended in 53 arrests, violence and public shaming by police, government and media.

Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives president Graham Willett said in the National Museum of Australia: “Many of those arrested were badly beaten inside police cells, and The Sydney Morning Herald sank to new editorial lows by publishing the complete list of names and occupations of those arrested.” The Herald has since apologised.

Since then, major legal and social milestones have been achieved. Sexual discrimination was banned in 1984, homosexuality was decriminalised nationwide by 1997 and, in 2017, the public overwhelmingly voted in favour of legalising gay marriage.

From humble beginnings in 1978, Mardi Gras has grown each year to become the monster festival it is today.

Controversial partnership

In recent years, as Mardi Gras has turned to commercial partnerships to fund its events, industry leaders in the queer community have split over the direction the organisation should follow.

Mardi Gras chief executive Jesse Matheson stepped into his job last November during one of the most turbulent times of the organisation’s recent history, with a vision to fix its finances.

Balancing the need to secure funding, manage a budget and remain strictly grassroots is no small feat, particularly for an organisation as important to the queer community.

Mardi Gras entered a partnership with Kicks Entertainment, a subsidiary of Live Nation, to deliver this year’s after-party event. The decision attracted backlash from those who believe the organisation should have partnered with a queer-led business.

Peter Shopovski from The House of Mince, a Sydney-based queer party promoter, said the party culture built by queer people following the 1978 march was never merely nightlife. It played a significant role in helping establish queer promoters, artists, political expression and community.

“The question is not whether [Mardi Gras] should evolve,” he says. “It absolutely should. The question is how its flagship events are stewarded.

“When custodianship of major events shifts away from long-term community stakeholders, it is natural for people to ask how those decisions reflect the festival’s protest origins and its ongoing responsibility to the queer cultural sector. This is not about individuals. It is about governance and legacy.”

Mardi Gras says it partnered with Kicks Entertainment to run its after-party, known as Party, to reduce financial risk.

“We engaged with a number of queer-led event businesses; however, Party is a large-scale event involving significant cost, complexity and financial exposure. To protect the festival’s sustainability, we must partner with producers capable of managing that scale,” a spokeswoman says.

Party canned

Less than a month before one of the most iconic events in the Mardi Gras line-up came a bombshell announcement.

“I was appointed CEO and tasked with renewing and reimagining the festival following two years of significant financial loss,” Matheson said. “A major contributor to that loss has been the Mardi Gras Party, which has run at a deficit every year since 2020 following the loss of the Royal Hall of Industries.”

“As part of stabilising the organisation, the decision was made to cancel … Mardi Gras Party.”

Matheson said the decision was not taken lightly. His organisation’s future was “facing an existential threat” – especially with future sponsorships uncertain and the withdrawal of a headline artist that would’ve been the largest since Cher. “It was absolutely the right decision,” he said.

Behind the scenes, conversations about Party’s future were taking place well before the public announcement, with Matheson acknowledging community grievances about expensive ticket prices in his statement.

Louis Hudson, a Mardi Gras board member whose tenure finished in November, said that while he was disappointed with the cancellation, he was also relieved.

“We were in a situation where we felt the best thing to do was to provide a party for the community,” Hudson said. “The 48-year history of the Mardi Gras party, for us, was paramount. If we had the ability to do it with a commercial partner, then I thought it was worth a go because the party model was broken. It wasn’t making any money.”

Hudson said Party’s crowds had been dwindling as tickets grew more expensive, space was lost (the Hall of Industries became Swans HQ) and queer independent promoters began offering alternatives.

“I think it has to downsize. We have to stop trying to kick for that 10,000, 12,000 goal. We have to bring it back to a 4000 to 6000-person party. That would probably fit the demand for Party to a smaller, more cost-effective venue than the Entertainment Quarter,” he said.

It is not the first time that funding issues have hit Mardi Gras. The charity lost about $1.2 million in 2024 when asbestos was found in Victoria Park, overshadowing its Bondi Beach party event and leading to a NSW government bailout of $1.1 million to prevent it from becoming insolvent.

“Since then, we’ve been on a bit of an austerity budget,” Hudson says. Corporate sponsors comprise about 10 per cent of the parade’s floats each year. The City of Sydney has contributed about $280,000 of value-in-kind between 2024 and 2027.

Destination NSW also funds the parade, though the amount is not disclosed. Independent Sydney MP Alex Greenwich said parliament didn’t receive a request for funds from Mardi Gras following Party’s cancellation.

Did Liberals try to ‘cancel’ Mardi Gras?

While Mardi Gras was in the throes of dealing with Party’s cancellation and a board feud, NSW Liberal arts spokesperson Chris Rath said it was being “hijacked by left-wing extremists” and called on the government to review its funding commitment.

Rath, an openly gay MP, was referring to the left-wing activist group Pride in Protest. “I called on the government to consider reviewing funding arrangements to ensure the organisation is operating in line with the expectations of the broader LGBTQIA+ community and the public,” he says.

The comments led to Labor MPs declaring they would never cancel or defund Mardi Gras. Although that wasn’t what Rath called for, Labor maintains it is what he meant.

“When Chris Rath listed his grievances and then called on the government to ‘review its funding commitment’, he was not proposing an increase in funding; he was threatening its future,” Arts Minister John Graham says.

Greenwich says Rath’s comments are: “Out of touch, just as his party’s position on LGBTQ rights is out of touch.

“Let’s not forget that the Liberal Party and Chris Rath, unlike Felicity Wilson, voted against the LGBTQ equality bill. I would much rather they spend their time listening and supporting the community when we need it, not seeking cheap political shots.”

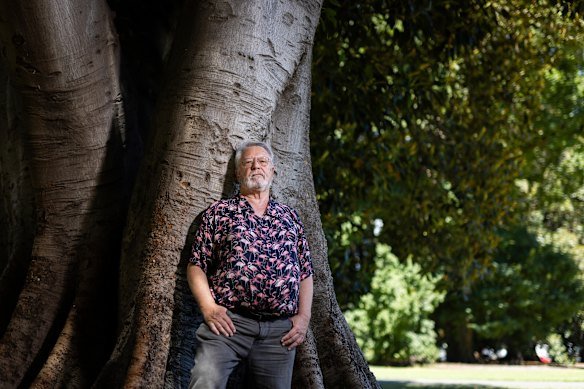

Ken Davis, an organiser and attendee of the 1978 march, said the Liberals’ comments were part of a broader conservative culture war on the arts. He also said that NSW police actions at a Town Hall Palestine protest felt similar to 1978.

“In the first Mardi Gras and in the subsequent protest, police contained legal, peaceful assemblies, like what’s now called ‘kettling’. They then told people to disperse, but there was no way to disperse, and people got arrested. That’s what happened at Sydney Town Hall the other day at the anti-Herzog protest, and the laws against protests now are worse than before,” he says.

“We campaigned, and we got the summary offences law changed, so the idea that protest is illegal unless the police say it’s OK, and that the police have power to contain people and simultaneously force them to move on, this is going back to the worst moment of Mardi Gras.”

In a separate blow to this year’s parade, Jewish LGBTQ+ social group Dayenu decided not to participate for the first time in 25 years, citing antisemitic safety concerns.

Factional fighting

Underpinning much of the political debate in parliament is the emergence of socialist activist group Pride in Protest.

The organisation has two Mardi Gras board members, Luna Choo and Damien Nguyen, and holds a voting bloc of about 20 per cent. Its campaigns often take an oppositional stance to Mardi Gras decisions – deeming them not progressive enough – and have raised the ire of many members, including some who formed an opposing faction.

Protect Mardi Gras, established by 78ers Peter Murphy and Peter Stahel, was formed last year to counter Pride in Protest. They supported three board members in the last round of elections, including co-chair Kathy Pavlich.

“Our festival would not exist without sponsors or government,” Stahel says. “Pride in Protest don’t want everyone included; they want a purity test.”

Pride in Protest member Charlie Murphy said Protect Mardi Gras only talk about inclusion when referring to institutions that are “screwing us over”.

Across 17 days in January, a board feud erupted between co-chairs Pavlich and Mits Delisle, and Choo and Nguyen.

It began after the board decided not to implement three motions filed by Pride in Protest, and resulted in the co-chairs and activists trying to censure each other. Delisle and Pavlich were successful in censuring Choo and Nguyen, but misgendered Choo, who is a transgender woman, in their motion.

“From calling me a man in the motion notice, censuring all pro-trans directors two weeks from season, to continually blocking support for transgender rights calls from members,” Choo says. “This is bigotry masked in corporate-speak.”

Delisle has since apologised.

“With turbulence comes change,” Hudson says. “I think the community is not going to let Mardi Gras fail.

“I think every director around that table, regardless of where they came from politically, acknowledges how formative Mardi Gras is as a space for a young queer person to feel at home for the first time.”

Hudson says that after attending his first parade, “I had this gut-wrenching feeling like, ‘Oh god, I’ve got to wait for a whole other year for it to happen again’.”

This is the feeling Stahel says he wants to protect. “Many people are overwhelmed by the sense of belonging at the parade. You can be a socialist, an anarchist even, and it doesn’t matter. You are welcome.”

It is an event where queer rights are still being fought for, Greenwich says. “The reality is, in NSW, a teacher or a student can still be kicked out of a private school because of their sexuality.

“But today, we celebrate our community.”

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Read the full article here