Every ending has a beginning.

Come Anzac Day, come the marching, the speeches, the tributes, the laying of wreaths, the shaking of heads as time conquers even the bravest who served. “Lest we forget” will be said, quietly, sincerely. Salvos will cut the sky, bugles will sound the music of the military.

Yet there is a parallel world that moves through this day. It is the shadowland inhabited by those who served this country. It is a land defined by its loss, a hell that is too often cloaked in silence from the other world.

This Anzac Day, a mother in Adelaide will place photographs of young men at the base of a cenotaph, as she has at other cities over the past few years.

In Melbourne, a man will sing to an audience a new song he has written.

Both step from one world to the other. For the woman, she does this because of the undying love for her son, and for all those whose lives ended on the same path as his.

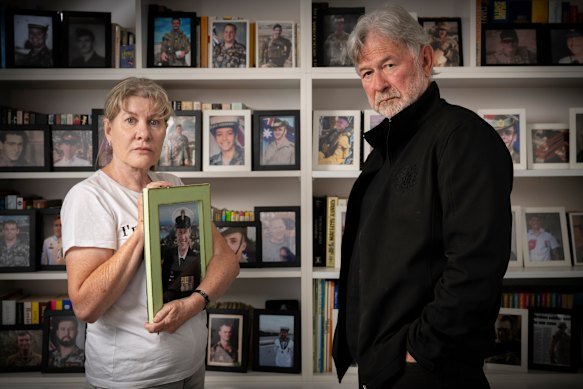

Her name is Julie-Ann Finney. Her son is David Finney. David’s father, grandfather and great-grandfather all served; his great-grandfather, Albert, at Gallipoli.

David was a petty officer and technician in the navy, where he spent virtually all his adult life. He killed himself in 2019 at the age of 38. He loved the navy, but some assignments, such as those involving asylum seeker boats, deeply affected him. The plight of the children was like a “dagger to the heart”. His death was Julie-Ann’s ground zero, and her spark to fight and try to find a light in the shadows for the thousands of other servicemen and women who have died by suicide.

Last December, the federal government delivered its response to the Royal Commission into Defence and Veterans Suicide. Julie-Ann was a prime mover in getting the commission established. For three years, she sat through every session of the commission’s hearings around the country. She lobbied, protested and called with every breath for something to be done.

David Finney was a petty officer and technician in the navy.

Defence Minister Richard Marles, in speaking of the commission’s report to parliament, acknowledged her role: “I know… that this report would not be tabled today but for Julie-Ann’s advocacy … her advocacy has been singularly brave. I want to say to Julie-Ann, that this report is for David, and for the many others like him who have worn our nation’s uniform.”

From 1985 to 2022, there were 2007 confirmed deaths from suicide among Australian Defence Force members and former members. From 2011 to 2021, an average of 78 serving or ex-serving members died by suicide annually. These numbers are only approximate, as the commission has noted the number of suicide deaths of Vietnam veterans was not included. It’s estimated the true number is about 3000.

The report recommended establishing an agency that seeks reforms that prevent suicides, and within the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, an agency that helps with the transition from military life to civilian life. But to Julie-Ann, acknowledgement is not meaningful action. The machine of bureaucracy that built the toxic culture within the Defence and Veterans’ Affairs departments cannot be part of the solution. Her cry is, “Don’t enlist until it’s fixed.”

When she heard the royal commission was being set up, “I cried so much, and not tears of happiness; tears of trauma would be closer to the truth. I had to sort through my feelings … I came to the realisation that this was not the achievement many had hoped, it was step one of a fight that would not end easily. The recommendations, from my point of view, were very close to ‘exactly’ what was needed. But as always, politicians, Defence, DVA [the Department of Veterans’ Affairs] and ex-service organisations were able to tweak and spin every word to suit themselves.”

It’s a cruel irony that in 2016, David featured in an advertisement for military life – and in December that year attempted suicide.

Julie-Ann loves those who serve their country. She doesn’t love the country’s treatment of them. When David enlisted, she was told her son was now part of the family. It’s a hurt that won’t go away, for how could family treat its members so?

In Julie-Ann’s evidence to the commission, she writes: “In December 2017, David was in hospital. He was very unwell. He was given a discharge date from the navy with effect on 12 December 2017. There was no understanding of why that date. He was still in hospital and needing help. David was lying in his hospital bed, unwell, broken, trying to recover from what was a life-threatening medical condition and the navy discharged him from service. They discarded him. They abandoned him like he was a broken piece of machinery that was no good to them any more. Apparently, he wasn’t ‘family’ enough that they would look after him.”

Julie-Anne Finney, with a photo of her son David, and singer-songwriter John Schumann in front of pictures of service people who have taken their own lives.Credit: Ben Searcy

On the eve of this Anzac Day, she says: “How do I keep telling people if you serve or have served, I’m grateful. I’m proud. However, with more than 3000 dead, I will keep saying and keep campaigning for ‘don’t enlist until it’s fixed’, and for those that think I’m playing with national security, simple, fix it.”

“I would rather our kids not join the military that have them join and then not be able to live because of a trauma-inducing culture. I truly believe that the ADF have zero idea what they are throwing their members to when they discharge. But those members have been destroyed and discarded and many die.”

Julie-Ann says she is contacted about 100 times a week by veterans. Some are suicide calls.

To those who ask why she doesn’t highlight good stories of serving, she replies: “Because they [good stories] don’t need fixing and there are thousands and thousands of bad stories to be told, and they just keep coming.”

Every ending has a beginning.

Singer-songwriter John Schumann is the man singing on Anzac Day. His song, I Was Only 19 (A Walk in the Light Green), is now part of commemoration services. It was written 40 years ago about 3 Platoon, A Company, 6RAR, as both an homage to those who served in Vietnam and a lamentation to what happened to them after the war. It is every Vietnam veteran’s tattoo.

The new song Schumann will be singing on Friday at the Essendonian pre-Anzac Day match arose from the commission’s report and the battle being waged by one woman to have her son’s and every other mother’s son’s fate made known – Julie-Ann Finney.

The song is Fishing Net in the Rain (Schumann wrote the lyrics from music by friend and manager Ivan Tanner). “While the song was inspired by David Finney, it’s really important to note that this song is about – and for – the thousands of current and former members of the ADF who have taken their own lives after serving Australia. And, perhaps more importantly, it’s for their families,” Schumann says.

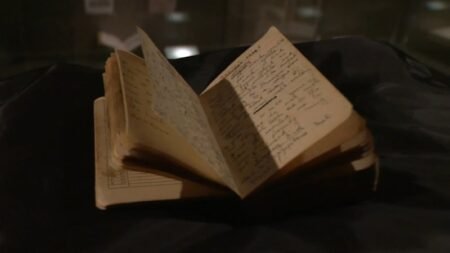

It was to put a human face to the commission’s findings. Schumann says he would be “incandescently angry” if similar treatment had happened to a child of his. He contacted Julie-Ann, who gave him access to some of David’s possessions. He found that top of David’s music streaming list was I Was Only 19. Another Schumann song, Safe Behind the Wire (also about vets), was there as well.

The video clip of Fishing Net in the Rain begins with this extract from one of David’s last social media posts before he took his life: “If it’s not one thing it’s something else. I’m running out of ways to forget. I’m running out of ways to heal!!! I want more answers. Better solutions because sometimes I feel like I’m catching all the answers, sometimes it’s like holding a fishing net in the rain.”

Away from music, Schumann spent about a decade making presentations to workers at remote mining and construction camps in South Australia and Western Australia about mental health. “Suicide is an immensely difficult and delicate topic. I’m no psychiatrist or psychologist but I know from my clinician friends that people don’t want to end their lives. They just want the pain to stop,” Schumann says.

He cites an extract from a former airforce member highlighted in the executive summary of the commission’s report: “Nothing will take away what it does to a person to literally sign a piece of paper to say they will go anywhere at any time and do anything – including sacrificing their own life – in the defence of our country. And then for that country to turn around and say to them they are not worth anything to them broken. Not worth anything to them injured. That they see me as nothing.”

Julie-Ann says the song is for those grieving and she hopes it “will give some level of understanding to civilian Australians. The song is for families and friends bereaved by veteran suicide, so it is for thousands. If we don’t hear people like me, the song will be for thousands more.”

As to the bureaucracy and the networks of organisations associated with the military, Julie-Ann as part of her mission seeks the dismantling of the Ex-Service Organisation Round Table, which she describes as “a tired and failed group of organisation presidents who have consistently failed veterans”. She has set up a petition for it to be disbanded.

Of the politicians and the services establishment, she has found, “They listen, they nod their head. Then no one does anything. I won’t go away. You took my son. I can’t stop.”

The veterans who have died by their own hand can no longer speak for themselves. Julie-Ann Finney has a voice. She demands to be heard.

As to Schumann, how can he stop from singing? The vets are not numbers. They are people – flesh and blood, hearts and souls.

Every ending has a beginning.

Lifeline 13 11 14

If you are a current or former ADF member, or a relative, and need counselling or support, you can contact the Defence All-Hours Support Line on 1800 628 036 or Open Arms on 1800 011 046.

Read the full article here