Using the combined data, women can add their age and the number of eggs that have been retrieved and receive estimates of the likelihood of them having at least one, or at least two, children using their eggs.

Fertility specialist Dr Raelia Lew said women want more transparency around egg freezing success.

“The calculator presents three separate estimates based on distinct data sources,” said Gardner.

“Two are drawn from peer-reviewed published studies [one Spanish and one American], while the third is based on aggregated clinical outcomes from Virtus Health’s IVF clinics, reflecting real-world data from a large, contemporary Australian patient population.”

The calculator models outcomes across egg thawing, fertilisation, embryo development, transfer and implantation, “and is statistically adjusted for complex patient profiles”, he said.

The two large international studies were conducted in 2016, before the rapid-freezing method vitrification was in use. It dramatically increases egg survival rates after thawing and has led to higher live birth rates.

Loading

The calculator illustrates that women who freeze eggs younger and have more eggs frozen have much better odds of having babies with them, but longtime researcher, Karin Hammarberg, says younger women are the least likely to return to use their eggs.

“Only about 11 per cent of women return to use their eggs … and the younger the woman is when she freezes her eggs, the less likely she is to ever use them,” she said.

“The bottom line is that younger women with more stored eggs have the greatest chance but are also the ones least likely to ever need or use their eggs.”

She said the calculator showed contemporary success rates at Virtus clinics, including Melbourne IVF, were better than those reflected in the international studies, but that up-to-date data from other Australian clinics could be comparable.

Melbourne IVF medical director Dr Raelia Lew said women wanted more transparency about egg-freezing success rates, but that awareness of age-related fertility decline remained low.

“The best thing I can do for my patients who freeze their eggs is counsel them realistically,” she said. “This [calculator] is about realistic counselling, not convincing more women to freeze eggs; it’s about helping women who freeze eggs to create a resource that is meaningful to them.”

The calculator is the first of two to be available to Australian women; Melbourne University researchers are studying what information women want about egg freezing. That data will be used to create a calculator being developed by the Australian and New Zealand Assisted Reproduction Database, run by the University of Sydney.

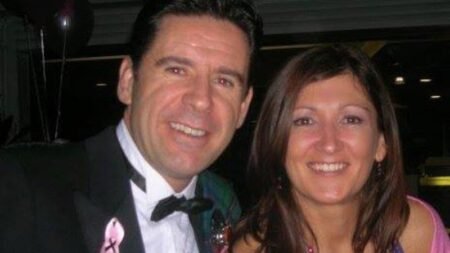

Although she works in health communications, Alana Jones, 36, recalls feeling shocked when she saw a chart showing the female fertility timeline illustrating the decline in egg quality after the age of 35.

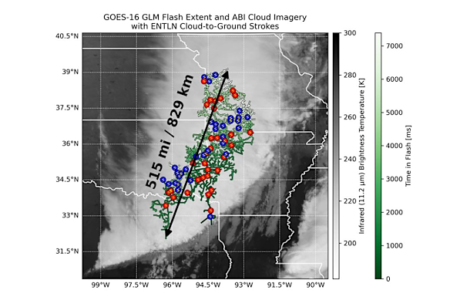

“It was very compelling seeing that data; you kind of know it, but when you actually see the graph, like a dramatic drop-off, it’s quite staggering,” she said.

At age 36, women have half the chance of conceiving naturally that they would have had at age 20. By the age of 41, the rate per month of conception among couples trying falls to 4 per cent.

Jones learnt in her early 30s that she had inherited a rare genetic disorder affecting the “powerhouse” of human cells, the mitochondria, from her mother. She froze 50 of her eggs at the age of 34, intending to use them when Australia’s planned mitochondrial donation scheme begins.

“This condition is maternally inherited. My mum had it, and she died from this disease. So finding out that I … would be guaranteed to pass it on to my child is not something I was willing to do after watching Mum suffer for so long,” Jones says.

“I wouldn’t be willing to have children without this process, I just couldn’t pass on this disease.”

Get the day’s breaking news, entertainment ideas and a long read to enjoy. Sign up to receive our Evening Edition newsletter.

Read the full article here