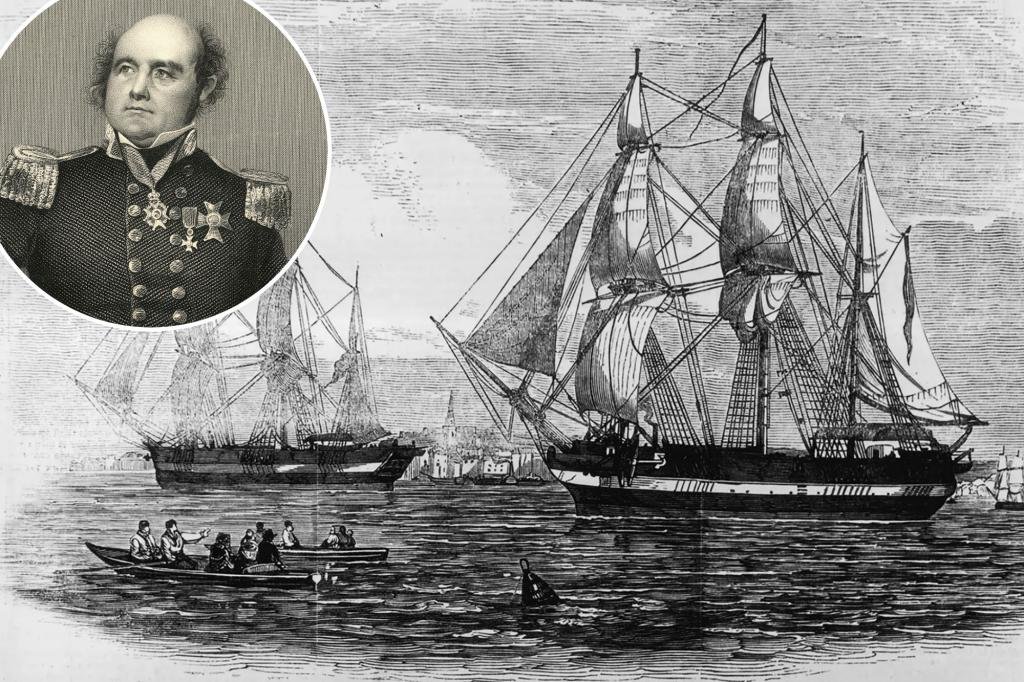

In May 1845, one of England’s most storied naval officers, Sir John Franklin, launched an expedition to discover the Northwest Passage.

Once thought to be ice-free, the legendary North Pole journey had been mythically described — without any real evidence — as an earthly paradise with palm trees, dragons, and 4-foot-tall pygmies.

Forget about blizzards, polar bears, and Arctic typhoons.

But, Franklin and a crew of 128 men never made it out of the great Northwest.

And what became known as “the Franklin mystery” has led to more than 175 years of speculation and “spawned generations of devoted ‘Franklinites’ obsessed with piecing together the story,” writes New York Times bestselling author and adventurer Mark Synnott in his travelogue-mystery, “Into the Ice, The Northwest Passage, the Polar Sun, and a 175-Year-Old Mystery” (Dutton).

Synnott, a veteran of international climbing expeditions, including in the Arctic, Patagonia, the Himalayas, the Sahara, and the Amazon jungle, had become obsessed with what really happened to Franklin and his crew.

Thus, he embarked on his 40-year-old fiberglass boat, Polar Sun, from Maine through the Northwest Passage in order to witness what Franklin encountered some nearly two centuries prior.

His greatest hope was to find the famous skipper’s records and diaries, possibly on King William Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, where Franklin’s two ships became stranded in 1846 and froze in the sea ice just north of the island that lies between Victoria Island and Boothia Peninsula.

“Nearly every shred of the Franklin expedition’s recorded history has been lost to the winds of time and . . . the story of Franklin’s expedition is one of cannibalism and chaotic disintegration of order although one small band may have survived for years,” writes Synnott who confesses he got caught up in his own “morbid fascination” with what happened to the skipper who was left stranded in the central Arctic.

Franklin’s tomb and logbooks are still out there.

Finding them would be like finding the Holy Grail, writes the author. “I had in fact climbed Everest, and now here I was apparently going for the sailing equivalent.”

Synott never found Franklin’s frozen resting place, but he learned that he had died on June 11, 1847, two years after leaving England.

Moreover, some 105 survivors from his crew crossed the ice and tundra, dragging their boats and hoping for open water.

“But one by one, every single sailor must have succumbed to a variety of maladies including, we can assume, starvation, tuberculosis, scurvy and trench foot,” writes Synnott as he sat with his own crew members looking over the open ocean and pack ice.

It was here where Franklin’s crew likely deserted their ships and headed off on a doomed death march, ignorant of the dangerous polar bears that traveled across the treacherous ice floes.

They likely had even less knowledge than the nomadic Inuit people who had lived in the north for more than 4,000 miles, traveling with the seasons via dogsleds and kayaks — facts the British chauvinistically believed they were discovering for the first time.

The Inuit people knew how to eat “Greenland food — the seafood, sea and whale oils, and fatty meats that prevented scurvy when there were no fruits and vegetables.” In the same locale, members of Franklin’s expedition starved and were forced to eat other crew members.

In 1854, Dr. John Rae of the Hudson’s Bay Company discovered that Franklin and his ships had become trapped in ice since September 1846, and Franklin died nearly a year later.

The explorers had left notes in tin containers they buried under rocks on King William Island confirming that 24 other crew members died and the 105 remaining survivors abandoned ship and headed south toward Back’s Great Fish River.

Traversing the ice-bound sea lane across the Arctic Ocean connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans had long been a dream of explorers as a shortcut to the Far East, and for England, this northern route could break Spain’s colonial-era stronghold on world trade.

When John Barrow, secretary to the British Admiralty made the offer in 1844 of 20,000 pounds sterling — the equivalent of $2.5 million today — for the discovery of “a northern passage for vessels by sea between the Atlantic and Pacific,” Franklin was chosen to lead the voyage although he was 59 years old at the time and retired for 18 years.

Franklin had been to the Arctic three times and was a famous and deeply respected explorer nicknamed “the man who ate his boots” after half his crew died on his first expedition and he ate his own boot leather to stay alive.

This time, he set sail with stores of 7,000 pounds of pipe tobacco, 3,600 gallons of 135-proof West Indian rum, 5,000 gallons of beer, and a daily food allowance for each sailor of three pounds of grub.

Franklin mania consumed the British public, and expeditions and search parties were sent out only to find mutilated corpses.

In the end, writes the author, “The Inuit held the keys to this kingdom . . . they had long ago explored every inlet, strait and island in this Arctic maze. All the explorers had to do was ask.”

Read the full article here