Updated ,first published

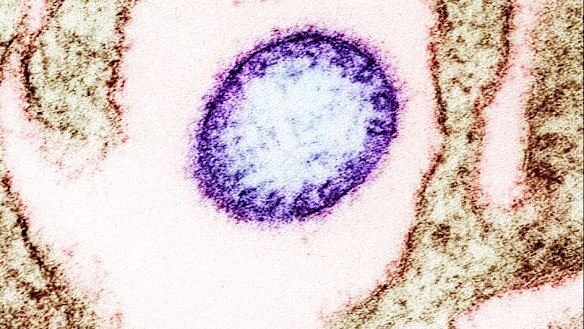

Health Minister Mark Butler says Australia is monitoring an outbreak of the deadly Nipah virus in India “very, very closely” after the country’s neighbours ramped up their border protections to avoid any further spread.

Two cases of the virus, which has no vaccine and a mortality rate between 40 and 75 per cent, have been confirmed in West Bengal. India’s health ministry said this week that authorities have identified and traced 196 close contacts, who all tested negative and showed no symptoms, but Australian authorities remain on high alert.

“The Nipah virus is very rare, but it’s also very deadly,” Butler told Today. “The Indian authorities tell us they’ve got that outbreak under control, but nonetheless we’re monitoring it very, very closely because this is a very serious virus.”

The Nipah virus exists in fruit bats but can spread to other animals, especially pigs, and people.

Flu-like symptoms, such as fever, headache, or vomiting, usually appear between four days and three weeks after infection. Some people develop pneumonia, and in severe cases, symptoms of encephalitis – inflammation of the brain – including confusion and sensitivity to light.

The virus most often spreads to people through contact with infected animals or their bodily fluids, or by eating fruit contaminated by animals. It is less commonly spread between people unless there is prolonged contact.

West Bengal shares a border with Bangladesh, where there have been 347 cases of Nipah virus infection in humans and 249 deaths between January 1, 2001 and September 9 last year.

The two confirmed patients are health workers – a male who is recovering and expected to be discharged from hospital soon, and a female patient in a critical condition, the West Bengal chief district medical officer said on Thursday.

Butler said human-to-human transmission was difficult, and the virus did not spread through airborne particles like COVID-19 or the flu.

“It really needs quite close personal contact, so it’s spread through essentially human fluids,” he said.

Butler said the Nipah virus had never been detected in Australia, and the government was satisfied existing protocols for sick travellers arriving in the country were sufficient, but would consider further measures if recommended.

“We’ve got no advice to change those protocols at this stage, but we’re monitoring on a daily basis. This is, as I said, a very rare virus … but if you do get it, the mortality rate is very, very high – between 40 and 75 per cent. We’re taking it seriously, but we’ve got no advice at this stage to change what are already very clear protocols.”

Those procedures include screening for symptoms of sickness on arrival, a spokesperson from the newly established Australian Centre for Disease Control said.

“Existing protocols also ensure that any identified ill-traveller can be assessed quickly and referred to jurisdictional health authorities, where appropriate,” they said.

“Australia has appropriate diagnostic capacity to detect Nipah virus in reference-level public health laboratories, as well as at the Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness in Geelong.”

The spokesperson said those travelling to affected areas should avoid sick people, potentially contaminated animals and fruit, especially raw date-palm sap, and practice good hand-washing hygiene.

“[Travellers] should avoid any contact with fruit bats and pigs, the main carriers of the virus, or eating any fruit that appears to have been partially consumed by an animal. Fruit should be cleaned and peeled before it is eaten,” they said.

They said the organisation worked closely with the Department of Health and Australia’s border agencies to assess the risk of international communicable disease outbreaks.

Pakistan is the latest country, joining Thailand, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam, to tighten screening at airports.

University of Sydney professor of virology Eddie Holmes, an expert in the evolution and emergence of infectious diseases, said it was unclear why these cases had sparked so much interest abroad, given Nipah cases had been reported almost every year across Bangladesh, India, Malaysia and Singapore since the first reported human case in 2001.

“At the moment, I don’t see any reason why countries have raised their level of concern and border security measures,” Holmes said.

“The Bengal authorities think they have contained it, and they have tested 196 contacts of the two cases, and all were negative, which shows you that human-to-human transmission does not readily occur.

“The only thing that is a slight question mark is that the two confirmed cases are hospital healthcare workers, so they are unlikely to be the index case, and there were likely more infections before the healthcare workers were exposed.”

Dr Alison Peel, from the Sydney Infectious Disease Institute, also questioned why these cases had garnered attention, noting “spillovers” of the virus from animals to humans occurred annually.

“There is no history of international spread of Nipah virus … and no increased risk to Australia,” Peel said.

Cases in Bangladesh have been largely linked to people drinking raw palm sap, a juice collected in containers attached to trees where Nipah-infected fruit bats are increasingly foraging as human activity encroaches on their natural environments.

“It’s all about humans destroying natural habitats,” Holmes said. “That process is just going to continue, and climate change is going to make it 10 times worse.”

First discovered in 1998 in Malaysia, Nipah was the inspiration for Steven Soderbergh’s pandemic virus film Contagion. Though the 2011 thriller’s virus was “Nipah on steroids”: far more infectious – and causing more alarming symptoms – than the real infection, Holmes said.

In Australia, Nipah has not been detected among the fruit bat species (Pteropodidae or mega-bats) known to carry the virus overseas. Mega-bats carry several viruses, of which only two have jumped to humans (the other, Hendra, has been detected in Australian bats).

There is no vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for the Nipah virus. Burnet Institute bat virologist Dr Joshua Hayward said prevention relies on reducing exposure risks, early detection and high-quality supportive care.

“Continued global investment in surveillance, research and preparedness for zoonotic diseases is essential to reduce the risk of future outbreaks,” Hayward said.

With Reuters

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter.

From our partners

Read the full article here