When Isaac Herzog called, the full horror of Bondi was still emerging. Jeremy Leibler, upon hearing of a mass shooting at a Hanukkah celebration on Sydney’s most famous beach, had rushed back from a wedding to his Melbourne home. He was watching with growing despair the live TV pictures when the number of the Israeli president flashed up on his phone.

“I’m with you,” Herzog told the Zionist Federation of Australia president. “I’m with the community. We are here for anything you need.”

It was a welcome yet discombobulating message.

Australian Jews are all-too accustomed to offering their support to family and friends in Israel at times of war, grief and trauma. In the immediate aftermath of October 7, Leibler travelled to Israel with a small delegation of Australian Jewish leaders and visited Beit HaNassi, the president’s residence in Jerusalem, to personally present Herzog with a statement of solidarity signed by more than 6000 Jewish and non-Jewish Australians.

As he listened to Herzog on the phone, the realisation hit Leibler with a jolt that Australia, a land known as a golden medina because of the security and opportunity it had long offered diasporic Jews, was now host to this same grief and trauma. Herzog made it clear that if it would help, he would come to Australia to show his support. This set in train an idea which will be realised on Monday when Herzog’s plane touches down in Sydney.

“The Australian Jewish community is used to giving support the other way,” Leibler reflects. “When the president called and said ‘we are with you’ it really struck me. I thought it would be profoundly meaningful for the Jewish community and be a powerful gesture from the government to extend a formal invitation.”

Leibler, whose family has personal ties to the Israeli president stradling three generations, shared with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s office what Herzog had told him. On December 23, nine days after Bondi, Leibler wrote to Herzog, on behalf of the Zionist Federation of Australia, with a formal invitation for him to come to Australia to meet with the families of Bondi victims and the Jewish community.

That same day, Albanese spoke directly with Herzog. After the call, he publicly announced his intention to issue through the Governor-General his own invitation for Herzog to be welcomed here in a rare, state visit, while Herzog simultaneously announced that he would accept.

In the space of nine days, Herzog’s offer of support had morphed into a significant statement about the depth of the Australia-Israel relationship and what this means to Australian Jews.

Welcoming the Israeli president to Australia does not signal a policy shift from Albanese towards the Netanyahu government. Australia’s disputes with Israel, whether concerning the war in Gaza, West Bank settlements or Australia’s recognition of a Palestinian state, are unresolved. The personal acrimony between Albanese and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, remains.

The Herzog visit signals that Australia’s recognition and support of Israel as a Jewish state and the connection nearly all Australian Jews have to Israel, whether religious, cultural or familial, transcends these differences. It is also a reconciliatory gesture towards Australian Jews who, before and after Bondi, felt abandoned by their government. “It is important, I think, for all to remember the reasons why the government has listened to the request of the Jewish community on this,” Foreign Minister Penny Wong said this week.

Herzog’s impending departure from Israel has re-enlivened debate across Australia’s conflict-weary Jewish population about whether his visit will salve the wounds of Bondi or open fresh ones. Either way, his public appearances in Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne will be accompanied by heavy security in expectation of anti-Israel protesters and potentially, other more malevolent actors.

When Albanese greets Herzog, he will follow in the footsteps of Labor’s longest serving prime minister, Bob Hawke, who 40 years ago received Isaac Herzog’s father, president Chaim Herzog, after the Australian government kick-started an international campaign to rescind an odious UN resolution which, to the distress of Israel, had sat on the General Assembly’s books for more than a decade.

Known as Resolution 3379, it was a form of words endorsed at the height of the Cold War by the Soviet Union, its eastern bloc satellites and some of the world’s most notorious regimes such as Idi Amin’s Uganda and Gaddafi’s Libya, which equated Zionism with racism and racial discrimination and sought to impugn, on moral grounds, the existence of the Jewish state. Hawke described it as an obnoxious equation.

In 1986, Hawke introduced into the Australian parliament a motion which, with the backing of the Coalition parties and the Democrats and unanimous support of both houses, condemned the resolution and called for its repeal. Then foreign minister Bill Hayden, as a doyen of the Labor left, played a critical role in securing support for the motion across the ALP. “The equation of Zionism of racism is profoundly wrong, disruptive and unacceptable,” Hawke told parliament.

“In a region where insecurity and suspicion are strong where barriers between peoples have proved difficult to break down, it is highly counter-productive to insult the guiding philosophy of a people, especially one whose consciousness has been seared by the scourge of antisemitism.” Chaim Herzog welcomed the Australian parliament’s call to rescind the resolution – the first of any nation outside Israel – as a “noble and moral gesture.”

A year later, “Australian Resolution” as it became known, was adopted verbatim by the US Congress. US Senator Patrick Moynihan, who warned the UN General Assembly when it adopted Resolution 3379 that “a great evil has been loosed upon the world,” urged all Western democracies to follow Australia’s lead. The resolution was finally scrapped in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

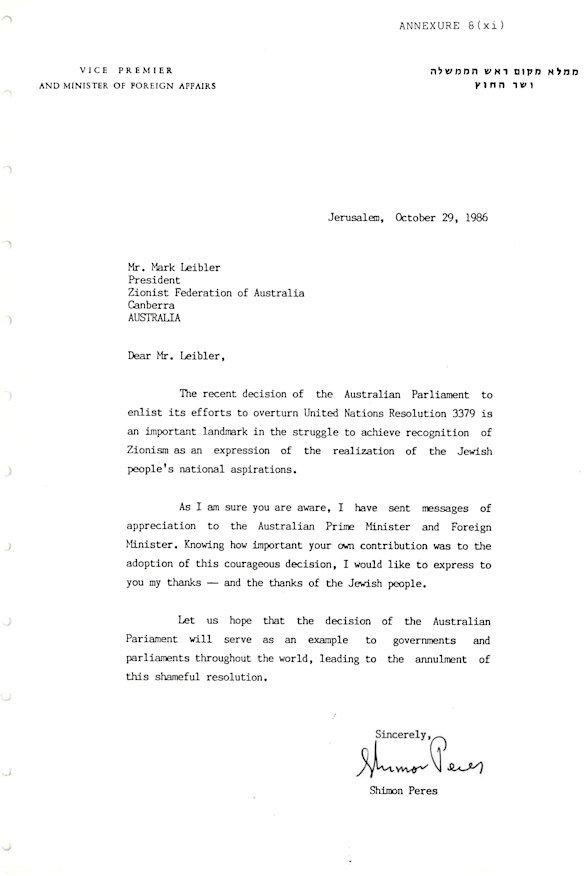

The story of 3379 and Chaim Herzog’s visit, which came within weeks of the parliament passing the “Australian Resolution,” is meticulously documented in the personal files of Mark Leibler, the father of Jeremy and a former Zionist Federation of Australia president.

The files contain letters from Hawke and Shimon Peres, a congratulatory telegram from Moynihan and a telex from a young Benjamin Netanyahu, who prior to his election to the Knesset, led Israel’s mission to the UN. It also includes a clipping of a forthright Age editorial, published to coincide with the Herzog’s visit, denouncing the UN resolution as “an insult to the memory of Jewish suffering” and a “slur on the state of Israel.” The resolution was scrapped in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Mark Leibler says this episode is relevant now, on the eve of Isaac Herzog’s visit because the crux of Resolution 3379 – an attack on Zionism as a proxy for Jewish people – is at the heart of antisemitism in Australia today. “It really resonates today when you look at what is happening,” he says. “The reason it was opposed and ultimately abolished is because it was nothing more or less than the demonisation of the Jewish people.” Equating Zionism with racism is no longer a UN resolution but is a ubiquitous slogan at pro-Palestinian protests.

Not all Australian Jews wish that Isaac Herzog was coming. Writing in The Jewish Independent, Melbourne lawyer Nomi Kaltmann, a teal candidate at the last state election in Victoria, said the president’s visit will aggravate her community’s essential problem; the conflation of Australian Jews with the policies and actions of the Israeli government.

Kaltmann argues that Herzog’s presence in Australia and inevitable protests will bring more “chaos and drama” to an exhausted community. “After two solid months of a relentless spotlight on our community, who has the emotional resources for another circus like this?” she asks.

“Israel’s president can and should be welcomed to Australia at the right time. But right now, our community needs space to heal, not another symbolic battleground onto which our grief and fear will be projected.”

Writing in reply, philanthropist and community activist Lillian Kline says this misdiagnoses the problem. “Jewish safety in Australia will not be secured by shrinking ourselves, lowering our voices, or asking for our grief to be handled quietly,” she says. “It will be secured when our leaders show up, when solidarity is expressed without hesitation, and when the legitimacy of Jewish life in all its complexity is affirmed, not negotiated.”

This will be a very different visit, in tone and context, to the sunny, relaxed trip Chaim Herzog enjoyed in November 1986, when toured Sydney Harbour with his wife Aura and laughed with Jewish youths children in the playground of Mount Scopus College in Melbourne.

Albanese, in his most expansive comments about Isaac Herzog’s visit, reminded people of its “solemn nature,” particularly when the president meets with the families of Bondi victims. This is an outreach of what, for the past two years, has been Herzog’s primary role; meeting with and consoling the families of hostages abducted on October 7 and IDF soldiers killed in the war.

The Israel presidency is apolitical and largely ceremonial. Herzog, a former Labor and opposition leader, cancelled his party membership to take up the role.

Professor Ben Saul, the chair of International Law at the University of Sydney and the UN’s Special Rapporteur on human rights and counter-terrorism, says Australia should be ostracising, rather than welcoming, the head of a state whose leaders have been indicted by the International Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity in Gaza.

The Gazan Health Ministry estimates that more than 70,000 Palestinians have been killed since October 7. The UN’s Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory has accused Herzog of contributing to this toll through a public comment he made within days of Hamas’ murderous rampage through southern Israel.

When asked by a journalist what would happen when rising civilian Palestinian casualties caused international public opinion to harden against Israel, Herzog responded: “It’s an entire nation out there that is responsible. It is not true, this rhetoric about civilians who were not aware and not involved. It is absolutely not true. They could have risen up. They could have fought against that evil regime which took over Gaza in a coup d’etat.”

In the same briefing, Herzog stressed the IDF would operate cautiously in Gaza and use “all means at its disposal” to reduce civilian casualties, including warning people and evacuating them in advance of military operations. He also added there were many innocent Palestinians in Gaza who didn’t support the actions of Hamas.

The commission found that Herzog’s comments “may reasonably be interpreted as incitement” to IDF personnel to attack all Palestinians in Gaza and recommended his prosecution by an international court.

The commission’s allegation, which Herzog denies, sits jarringly at odds with his reputation among parts of the Australian Labor Party and Australian Jewish leadership.

Herzog also provoked international condemnation for a photograph taken in December 2023, which depicts him scrawling a message on an IDF artillery shell to be used in Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. “I rely on you,” he wrote.

The Leibler family connection to the Herzogs stretches back 50 years to when Rachael Leibler, Jeremy’s grandmother, was the founding president of the Jewish children’s charity Emunah, and Sarah Herzog, the mother of Chaim Herzog, was the world president of the same organisation. Before Chaim Herzog entered the Knesset and later became president, he stayed at the Leibler family home whenever he visited Melbourne.

Alex Ryvchin, the Sydney-based co-chief executive of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, describes Isaac Herzog as a good, decent and compassionate man. “I know that foremost, for the (Bondi) victim families, to have him there and his wife, and to shake their hands and receiving their words will mean a great deal to them,” he said.

Kate Rosenberg is the executive director of the New Israel Fund in Australia, an international group which promotes democratic and social reform in Israel and the occupied territories.

She says that now that Herzog is coming, the pressing question is less whether he should than whether he will leave Australia with a full understanding of the complex and diverse opinions held by Australian Jews about his country. She points out that one of Herzog’s personal projects is a program called ’Kol Ha’am – Voices of the People – which is intended as an apolitical, international forum for Jews to express a diversity of views on serious issues.

“There is a silent majority of Jews in Australia who support Israel but not its government – the people but not the policies,” Rosenberg says. “Herzog as a figurehead presents an opportunity to separate those two ideas, but we also think his visit is an opportunity to remind him of what free and equal democratic rights for all people who live between the river and the sea looks like.

“The community is in pain and looking for support, wherever it can come from. It does feel good for some members of the community to receive that support from Israel and particularly from such a figurehead. But if he is coming we want him to hear what we have to say.″

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Read the full article here